Why are opioids such an addictive drug? How can we treat addiction AND mental health? Learn about the field of addiction psychiatry in this interview with Andy Chambers, M.D. of IU Health.

Transcript

(00:00) Phil Lofton:

From the Regenstrief Institute, this is The Problem. The Problem is an anthological podcast dedicated to fighting the hydras of healthcare, those complicated big, hairy issues that impact healthcare on the societal level. Every season you’ll hear about a different big, massive problem and each episode within that season will feature a different discipline or industries take on that problem, how it’s being addressed, how it’s being talked about, and the trials and triumphs of those involved clinically and personally. This season is all about opioids. Over the next few episodes, the problem, we’ll talk about how we local communities, Indiana and the United States got into this crisis, how people suffering from addiction are treated and how the needle can be moved on addiction. This is a podcast for anyone who might be interested in how these problems have developed and are approached. You don’t need a PhD to be affected by them, so you shouldn’t need a PhD to learn more about them. Regenstrief institute is a global leader dedicated to improving health and healthcare through innovations and research and Biomedical Informatics, Health Services, and Aging. Welcome to The Problem.

(01:14) Phil Lofton:

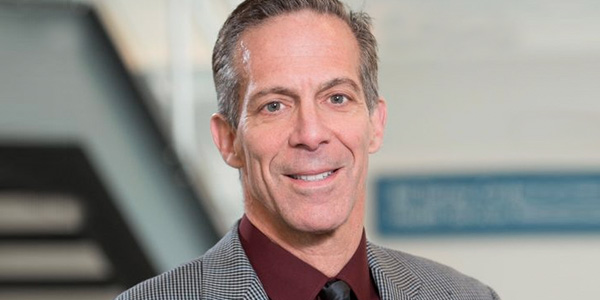

Hey, do you hear that? It’s kind of familiar. The baseline sure sounds like something I know, but it’s different. Today’s episode is going to be different too. Usually I’d have some parable about the discipline we’re discussing, but today I just want to get right to the meat of the topic. Do you ever have one of those conversations that just messes around with your understanding of time? I mean one of those conversations where you think it’s just been a few minutes and then you look at a clock and an hour somehow flown by. This is one of those conversations. Andy Chambers is an Addiction Psychiatrist with IU School of Medicine and Eskenazi Health’s Midtown Mental Health Center. For those of you taking notes at home, that’s the same organization as Ashley Overly from last episode. Doctor Chambers is a national leader in his field and he runs the addiction psychiatry fellowship at the school of Medicine. When we met up to talk, our conversation sped between topics touching on the past few decades and looking forward to what comes next. I want to hurry up and get right to it, but first things first. Welcome to The Problem. I’m your host, Phil Lofton.

(02:28) Andy Chambers:

How does addiction change the makeup of the brain?

(02:33) Andy Chambers:

Wow. So, we’ve learned a lot about this in the last 20 years. This is pretty recent science. What we’ve come to understand is that addictive drugs actually cause the disease through common pathways. What’s important to realize is that nicotine, alcohol, cocaine, opioids, amphetamine, these are all drugs that have different intoxicating profiles, right? They’re very different highs when you’re using them, but they’re all addictive and the way that they create the same illness of addiction is actually through more common pathways. The ways that the drugs overlap in their properties and one of the major neurotransmitters that is affected by all of these drugs is dopamine and that’s a neurotransmitter that regulates – this is really key – It regulates neuroplasticity and the part of the brain that controls motivation. So when I say neuroplasticity, I’m really talking about changes in wiring of neurons that governs learning and memory.

(03:52) Andy Chambers:

When you’re talking about motivation in a lot of people don’t realize at first until you really discuss this from a neuroscience level, but motivation is a, is a product of the brain, just like movement and emotion and sensation. Uh, so motivation is a product of the brain and it’s controlled or you know, involved with decision making. Um, it involves, you know, we call it freewill, sometimes willpower, all those terms apply to motivation and it’s a product of the brain. And as such, it’s capable of change when we grow up. I mean, we go from childhood to adulthood. Our motivation center of the brain evolves. It changes. We are motivated to do different things As we get older. Our behaviors are aligned differently as we get older and that’s natural and positive actually. So we know that system of the brain is capable of adaptation.

(04:52) Andy Chambers:

One of, again, one of the major transmitters that governs that adaptation, that rewiring that changes our motivation is dopamine. And unfortunately, all of these addictive drugs stimulate the neurotransmitter dopamine. So these drugs evoke a neuroplastic response in the motivation system. And, uh, what’s particularly devastating about that particular change is that it, um, it instills a motivation to use the drug. So, uh, as a person continues to use a given addictive drug, it’s creating a neuroplastic change in the brain that causes the person to want to use that drug a little bit more. And after that there’s a slightly increased probability they will use it again. And if they do, they use the drug again, another incremental neuroplastic change. And before you know it, it’s like a train that begins to build momentum coming out of the station at a higher and higher speed, um, this kind of interactive effect between drug intake, neuroplasticity, behavior change, drug intake, plasticity, behavior change, and it just, it’s a cycle and it gains momentum. And after a while someone is compulsively using even as they’re destroying many other precious things in their lives.

(06:25) Phil Lofton:

So to unpack that and to couch that an idea for an addictive context, because we’re going to be talking about it within the context of opioids, right? But some of the other contexts that people may be familiar about this with a would be like alcohol. That principle of tolerance, you have your first drink and your head spins, and then the next time to get that sort of reaction, you have to have two and four, and then the next thing you know, you’re downing the whole sixer during the night to get that same feeling. Yeah. With alcohol, there’s that sort of wall that you run into with the hangover. Sure. With opioids it’s a little bit more dangerous, right?

(07:02) Andy Chambers:

Well, alcohol is per dangerous too, you know, they’re there. It’s interesting you bring up alcohol, um, because they’re, they’re good to compare. It’s good that you brought those up. So where they’re similar is the alcohol and opiates, you know, people overdose and die on both drugs. It happens all the time. So they’re both lethal with a bigger overdose. Right? There are other addictive drugs are less lethal to overdose on. Um, both alcohol and opiates are sedatives, you know, they, they can knock you out if you do enough of them. So they’re both sedating and that’s different from say, nicotine or cocaine. Um, but in a head to head comparison, alcohol is a lot – It is addictive – but a lot less so than opiates, uh, and, and how do I, what’s my basis for saying that? Well, you know, about 80 percent of the US population are regular drinkers, um, but only about 15 percent have alcohol addiction, which is a high number, maybe 10 to 15 percent have some degree of alcohol addiction (NOTE: This survey is fascinating – lots of amazing data about drug/alcohol consumption!).

(08:08) Andy Chambers:

So only maybe one in eight regular drinkers have alcohol addiction (NOTE: See the survey linked above). That’s interesting, right? Because they’re irregular users of the drug, right? But only one in eight of that group actually has alcohol addiction. Whereas opiates is a different ballgame where once you become a regular user the likelihood that you also have addiction to that drug is much higher. What is it? Oh, it’s hard to say because the data is not very clear because it’s…that’s goes into another issue is that, you know, it’s prescribed for medical application, hence, you know, opiates for pain. And um, you know, the, the waters are very muddy there about how many people with pain on chronic opiates have opiod addiction. But let me, let me just hazard a guess that it’s probably, you know, the majority of people use opiates for whatever reason have addiction to those drugs too. The majority.

(09:09) Phil Lofton:

Wow. Yeah. And that is really interesting. So can we talk about from the neurological perspective why that is? Why are opioids so much more addicting than alcohol or then nicotine or anything like that?

(09:27) Andy Chambers:

Well, I’m glad you brought up nicotine probably on par with nicotine really. Nicotine is super addictive stuff (NOTE: the addictive properties are very well documented and culturally understood, but this NIH page is a good primer on how the addiction happens).

(09:35) Phil Lofton:

Wow.

(09:35) Andy Chambers:

Right? Yeah. Even though when that’s an interesting thing to bring up too, because you know, nicotine’s not really intoxicating, right? There’s not really a Super Fun, high? That goes along with nicotine. I mean, people feel something but it’s not a Super Fun, high? Necessarily like all these other drugs. And so that, that’s just an example where the addictive property of a given drug is not really related to the intoxication. Right, right. So, so addiction is not about intoxication at all. So in contrast, you know, with alcohol you can get super drunk.

(10:09) Phil Lofton:

Yeah.

(10:10) Andy Chambers:

But that doesn’t mean you’re addicted. So with nicotine, it’s another example of a drug, almost all regular smokers have nicotine addiction, but almost the only a minority of regular drinkers have alcohol addiction. So hence nicotine is much more addictive. And, part of that is like when you try to get people to stop, it’s a lot easier to stop drinking if you’re not, don’t have alcohol addiction. Whereas if you’re a smoker and you got nicotine addiction, very hard to stop. So let’s go to opiates because that’s, you know, so, um, you know, what, what makes different drugs have different degrees of addiction, a liability. And that’s true, you know, if you line up all these addictive drugs, really the three most addictive drug groups are nicotine amphetamines and, um, uh, opiates, opioids. So those are the three top (NOTE: Unable to find a citation for this particular ranking, but here you can read a paper discussing the addictive profiles of several substances).

(11:06) Phil Lofton:

Wow.

(11:06) Andy Chambers:

Yeah. And everything else has kind of lower, you know, um, cocaine’s a little bit lower. Although, you know, there are certain types of cocaine that get up with amphetamine. Marijuana is lower on the ladder, Alcohol’s lower on the ladder, but you know, they all have various degrees of addiction. So why are opioids among all these drugs at near the top? Um, couple of reasons. One is the effect of opioids in the motivational center of the brain is such that the addiction action happens through several converging pathways there. There are several ways in which opioids exert a cellular and pharmacological effect to generate this plastic change, right? So the same drug does it through different routes so that increases the potency of the addictive effect. So, another really interesting thing, um, that I think is probably somewhat unique to opioids. All there more research needs to be done.

(12:21) Andy Chambers:

And this is really fascinating, I think is it, you know, we all think about opioids and being pain relievers, right? That’s kind of the, it turns out in the last 15 years that we’ve begun to understand something very different is going on with the internal opiate system that we’re all born with. So we’re all born with this endogenous opioid system and we’ve understood that, that helps us internally regulate pain and other sensations without external drugs. When we’re young and, we’re attaching to our parents, same system is involved. So there’s actually a, the internal opioid system is actually part of the infant and the parent. Usually the mom beginning to form a basis of an attachment.

(13:12) Phil Lofton:

Serious?

(13:13) Andy Chambers:

Seriously.

(13:14) Phil Lofton:

Wow.

(13:15) Andy Chambers:

Yeah, yeah, yeah. It is amazing. It’s part of it.

(13:23) Phil Lofton:

So attachment between a mother and the child helps the child develop resistance to pain? Well, we’re unpack that. What does, what does that look like?

(13:33) Andy Chambers:

Maybe to some extent. Yeah, to some extent, yeah, there’s data to back that up. But the way the way people began to look at this is that, um, so think about this. This is the easiest way to see it. Okay. Right. People looked at how the children react. You know, how to young children react like, you know, toddlers or infants in a room when you, when the mom leaves the room, what does, what does a young infant do, how do they, how does a young infant with a healthy, a healthy young adult react when the mom leaves him?

(14:06) Phil Lofton:

Well they cry.

(14:06) Andy Chambers:

They cry and you know, they shake, you know, this is reaction. And so people began to look, wait a minute, there’s a lot of in what this baby’s doing that looks, you know, the blood pressure might go up a little bit of the baby cortisol, stress hormones go up and the baby, you know, is, not like crying but may seem some mucus coming out of the nose with the reaction red face, whatever, and, and along the way, someone` was like, wait a minute, that looks like opiate withdrawal, doesn’t it? It mimics a lot of opiate withdrawal. And so people started thinking about, you know, is there a way to understand the Bible, the brain biology of attachment to one’s mom that could relate to the functioning of the endogenous opioid system.

(14:53) Phil Lofton:

Wow.

(14:54) Andy Chambers:

Yeah, yeah, I know. It’s cool. It’s cool.

(14:59) Phil Lofton:

So, um, to, to follow up on that, I, one of the things that, the research that you sent over to me know, really hammered home is that when it comes to addiction psychiatry, we need to do more research for sure. Um, there’s a huge gap of research, but what does that, what does that say about babies that are born with nas? How does that play…

(15:21) Phil Lofton:

Hey, it’s Phil. I’m just jumping out of the conversation real quick. NAS, what I mean when I say that is neonatal abstinence syndrome. We talked about that in episode three with Dr. Litzelman and Carolina, it is a disease that affects babies of women who, uh, used opioids while they were carrying a baby. Okay. Just thought I’d clarify that back to the conversation.

(15:48) Phil Lofton:

Born with NAS. How does that play into it at all? It all. Does that play into it at all?

(15:51) Andy Chambers:

Well It’s concerning, isn’t it? And we. The thing that’s a troubling is that the current epidemic, which really got very large in very, very large in 2008, maybe even a little bit earlier and we’re still now, it’s gotten bigger since 2008. So I mean that’s a firm right now, a baby born and one that’s a 10 year old child. And we, we at that even in a way we weren’t really keeping good data about NAS babies. So at that time even it was happening were just not tracking it. Now there’s much more attention and we kind of have a better handle on what babies are now being born with NAS and there’s lots of them and so, but we don’t have the future result yet. Yeah. So we don’t really know. It’s not really well studied. What is the longterm impact of NAS.

(16:52) Andy Chambers:

I mean a parallel is, you know, fetal alcohol syndrome, but now we’re going to have something probably a little different than that. I’ve actually encountered, or beginning to encounter patients who tell me that they were, they were diagnosed with that as babies now who are in their early twenties. Right.

(17:12) Phil Lofton:

Wow.

(17:12) Andy Chambers:

And that’s the first time I’ve encountered that. Right? I mean, so that person who I’m thinking about is in the early twenties, what they would have been born in late nineties.

(17:21) Phil Lofton:

Yeah.

(17:22) Andy Chambers:

Before the epidemic got substantial. And when I see this patient, you know, they have this patient I’m thinking about has a combination of mental health and addiction issues and it’s not possible for me to tease out what is the, what could be a residuum from NAS or what are the many other factors, right that are in this. So I think that’s a – I’m glad you brought that up because that’s just a huge unmet research need, man. That’s fascinating. Yeah. Okay.

(17:50) Phil Lofton:

So, um, I kinda want to glance off of something that you were talking about. Uh, you were talking about the longitudinal respect or the historical perspective of the epidemic and how it has evolved over time. One of the things that I’ve picked up in your work and your talks in your powerpoint presentations is how this isn’t necessarily entirely a complete and total responsibility of the medical system, but we sure didn’t help, right? I’m one of the words they use to talk about this as the iatrogenic origins of the opioid epidemic. So can you talk a little bit about that?

(18:27) Andy Chambers:

Yeah. You know, I, I have to say I do actually place a lot of responsibility, you know, it’s a complex puzzle, so it’s not, we can’t pigeonhole any one individual or group, but most of the responsibility for this epidemic does lie with the healthcare system, you know, and iatrogenic meaning, um, you know, causing harm or injury or disease while trying to deliver healthcare is, you know, a good description of this epidemic.

(18:58) Andy Chambers:

Um, you know, flatly the data is very clear that um, the over-prescribing, the mass prescribing of opioids in particular, but other drugs too, it’s not just opiates, but the, the mass prescribing of these drugs, you know, in, in the United States, really beginning this, started to really increase in the nineties, um, and got very large in the 2000s. So over…over about that 20 year span.

(19:27) Phil Lofton:

What was wrapped up in that?

(19:29) Andy Chambers:

Oh Gosh, several fundamentals I would say. So that talking about root causes. We have, in the United States had several things happen (NOTE: For even more discussion on this, see episode 2 and hear Kurt Kroenke’s discussion on pain as the 5th vital sign). Um, the mental health and behavioral health infrastructure. The workforce has been essentially a collapsing over about a 20, 25 year period. It’s not gone, but I’m talking, you know, hospital beds being eliminated, people going into psychiatry, the numbers diminishing, the amount of, uh, psychiatry that’s taught in medical schools. And it’s very ironic because of course our brain science has gotten richer.

(20:19) Andy Chambers:

So how is it that the clinical care of brain disorders in terms of psychiatry has been diminishing while our brain knowledge of it has only increased, but you know, health insurance coverage for these conditions has weakened and gotten harder to come by. So while that’s going on, um, you know, and that kind of big, it kind of began with deinstitutionalization in the sixties and seventies closing a state hospitals and um, at the same time you have the war on drugs, which was really of a political and cultural movement in the United States to decide we’re going to address the drug problem through criminalization. So think of those two things happening at the same time, right? The, the, the slow motion, sort of degradation of, of um, behavioral health care while criminalizing drug addiction. And no one knew that mental illness and drug addiction are biologically interconnected diseases of the brain.

(21:27) Andy Chambers:

So what you end up doing now is beginning to criminalize mental illnesses self. And as that begins to gather momentum, right? There’s even more stigma, right? More stigma creates more stigma. Fewer doctors want to go into that because these are criminals, not people who need, you know- or morality gets wrapped up in it. That’s part of stigma as you, you instead of viewing it as an illness, you view it as a moral problem and you don’t want to be around people with moral problems or associated with criminals or aid and abet, criminal activity, et cetera, et cetera. And so it really, um, I think created a setting where addiction is not viewed as a biomedical problem. It’s a moral and criminal issue and therefore it’s not in the domain of healthcare.

(22:17) Andy Chambers:

So if it’s not in the domain of healthcare, if. Right, yeah, if it’s not something doctors should be concerned with, then, you know, it’s not even a disease. Then you don’t have to worry about it. Right. So you just Kinda, uh, you might, you know, if, uh, if doctors aren’t aware of addiction, they’re not aware of the dangers of it. Not really being taught at some for jails and prisons to deal with then, you know, um, if you’re creating it, you wouldn’t even know it.

(22:48) Phil Lofton:

Right, right.

(22:50) Andy Chambers:

You know, I’ve seen documents where barriers to healthcare is a concern for addiction. Barriers for healthcare, you know, and these are federal documents, right? That and you know, from the early two thousands, that concern of addiction is a major barrier for people to get adequate pain relief or healthcare.

(23:14) Phil Lofton:

So does that tie in pretty well with the idea that you talk about in some of your work of pseudo addiction?

(23:19) Andy Chambers:

It does. Okay. It does, right. So pseudo addiction was a diagnostic construct that came about in the late eighties by some folks who felt that there are people in pain who need opioids and you know, they look like they’re addicted, but you shouldn’t even assume they’re addicted because that’s not humane. You should just go ahead and relieve their pain with opioids. And so if they look like they’re addicted, well it’s not real addiction, it’s fake addiction, pseudo meaning fake. So just you need to go ahead and diagnose fake addiction and give them more opioids.

(24:03) Phil Lofton:

Oh Man.

(24:05) Andy Chambers:

So this concept gathered a lot of steam and a lot of people glommed onto it. And this goes along with, you know, the pain as a fifth vital sign movement. Uh, I mean, no one doubts that pain is, you don’t want health healthcare where we are concerned with pain because that’s just a general form of suffering we’re trying to relieve.

(24:26) Andy Chambers:

But what the alliance that occurred was a linkage between pain and opiates kind of being the sole solution. Right? And when we know, um, that there’s – opiates are far from perfect, they got major downsides and there’s also other treatments, lots, lots, lots of other treatments for pain. Lots (NOTE: We’re going to REALLY get into this later this season). Oh yeah. So, um, you know, so, so, but this is kind of where the forces came together, um, with this pain movement. And, you know, honestly, another dimension which kind of fits in with all this is that our healthcare system has gotten pretty big businessy, you know, just a little bit of profit motivated a little bit, marketing and commercial and, you know, so-

(25:18) Phil Lofton:

I was gonna say, you can advertise pharmaceuticals anywhere in the world directly to consumers, can’t you (NOTE: This is most definitely sarcasm)?!

(25:26) Andy Chambers:

Exactly. Another change in our medical economy. Exactly right. So, uh, that’s another element to it. And um, uh, there’s, you know, I the paper that one of the papers you reviewed, uh, I think I sent you, um, it’s interesting because I had a little bit of a hard time getting that one published, right?

(25:46) Andy Chambers:

I had a hard time getting that published and one of the journals that ended up not accepting it until that one did you want to me to write something different. That was really… And they wanted me to write a big review article about how not treating addiction is one of the biggest businesses in America.

(26:02) Phil Lofton:

Oh Wow.

(26:03) Andy Chambers:

Right. And that’s a great topic. But that would take me five years to write and an even bigger, you know, that’s a big. That’s a big chunk to bite off, but someone else suggested that because it’s kind of true. Right. You know, and so, um, unfortunately part of the iatrogenic opioid epidemic is a lot about what’s happened to our healthcare system. Viz a viz how it operates and uh, you know, um, uh, you know, trying to grab market share, grab patients, making sure it’s as pleasant as possible, efficient, all those things, you know.

(26:43) Andy Chambers:

And so, um, and in many ways that’s, that sounds good, right? These are, they sound good, but I think the opiate opioid piece definitely was, uh, when you, when you leave out psychiatry and behavioral health and addiction, you’ve got a real crisis on your hands.

(27:00) Phil Lofton:

So, I want to get to where you think addiction psychiatry comes in as far as, because I saw one of the diagrams from one of your powerpoints specifically discusses how addiction psychiatry is part of the fixed to this at multiple points in the pipeline. But real quick before we do, I want to loop around from this paper to a second thing that you talk about that’s just as much a part of the problem as pseudo addiction, which is one of the ways that we talk about how people use medicine, self medication. It is a term that is ubiquitous. It’s everywhere. From sitcoms to, to CW dramas to academic papers. It is the term and it’s bad, right?

(27:43) Andy Chambers:

I think so in a certain way. In sense. Applied to addiction. Yes. And how it all developed that. So self medication I think is an accurate term. Um, and under certain circumstances, you know, if I get a headache and I take an aspirin to relieve the headache, I have medicated myself. If I have a, um, you know, if I have a flu bug or if I have a flu and I’ll take a cough suppressant of medicated myself. Right. What’s happened in psychiatry is that the, the labeling of addictive drug use in mentally ill people has been labeled as self medication. The problem with that is it labels the behavior as a act of treatment when it’s actually that behavior is a part of their disease.

(28:41) Phil Lofton:

Yeah.

(28:41) Andy Chambers:

So when you do that, when when professionals in psychiatry, for example, label someone with schizophrenia as self medicating with alcohol or cocaine or even nicotine, then it kind of gives them a way to label the behavior without having to treat it because they’re not even calling it a disease or calling it an act of treatment.

(29:00) Phil Lofton:

Right. But again, like just like you said earlier this podcast, to talk about that convergence of self-medication and addiction and how you’re creating this new mental disease in yourself, that’s horrible.

(29:18) Andy Chambers:

It is. In fact, the label is so inaccurate. Everybody has bought in to the label of self medication to describe drug using and mentally ill people. I’m talking about addictive drugs, so you don’t really call it addiction, but by definition it actually is. It actually is an addiction, so the drug use is causing even more harm.

(29:42) Andy Chambers:

Right? So you’re calling something as an act of medicine taking when in fact it is producing the opposite of what medicine is.

(29:51) Phil Lofton:

It’s not self-medicating it’s self harming.

(29:53) Andy Chambers:

It’s self harming. It’s self harming.

(29:56) Phil Lofton:

Wow.

(29:56) Andy Chambers:

Because it’s addiction. So it’s kept the whole construct of self medication is actually very similar to pseudo addiction in pseudo addiction, you’re calling something the opposite of what it actually may be in self medication. The same both involve addictive drugs. So you’re, you’re, you’re taking the eye of the medical community, one in psychiatry, the rest and pain treatment off of the ball, right? Which is actually a disease called addiction with both those constructs that are dominant. Or had been dominant.

(30:31) Phil Lofton:

Yeah. That is so interesting.

(30:33) Andy Chambers:

That part of this self-medication construct was actually propagated by the tobacco industry. Seriously. Pretty interesting.

(30:43) Phil Lofton:

Wow. Unpack that.

(30:46) Andy Chambers:

Well, this was actually unpacked by investigators who were taking advantage of the large tobacco settlement. Don’t know if you’re familiar with that, but the, um, the, you know, the states got together and Mellitus successful class action lawsuit against the tobacco companies for not being upfront about the extent to which they knew nicotine was super addictive. Um, so they had to pay the states and they still are. They’re paying Indiana millions upon millions or paying other states millions and millions of dollars in, in damages caused by nicotine addiction to the public health. This is still going on. Um, one of the things that they also had to do is surrender documents that documented some of the extent to which the tobacco companies were actually funding psychiatry and neuroscience research that was trying to promote the idea that nicotine is a cognitive enhancing and mood – mood, like an antidepressant for mental illness.

(31:58) Phil Lofton:

Wow.

(31:59) Andy Chambers:

Right?

(31:59) Phil Lofton:

Wow. So when we get that, like a visual, like we have in like the 1960’s in the 1950’s with the old movies of like, take the edge off a little bit. have a smoke. That’s where we get that from.

(32:10) Andy Chambers:

A lot of it. There’s something, there’s something really good for your psyche helps you focus or a, you know, it’s an antidepressant, helps you be in control, happy, powerful, anything. I think that’s positive. You know, it gets linked and you can see it on the cigarette. You can see this stuff on the cigarette marketing packaging. So this investigator, I’m actually, she at the time was at UCF SF. Her name is Prochaska. Jodi Prochaska was one of the authors on this paper that unpacked is to use your words, such a good one, unpacked this evidence showing that the tobacco companies were, were connected in supporting research that was aiming to paint tobacco and nicotine in a positive light for mental illness. And it affected a lot of things. A lot of money went into this and it kinda was the only game in town.

(33:11) Andy Chambers:

There was no other theory other than tobacco is in some way a medication for mental illness because that was the only hypothesis that was being funded, right? There was no other hypothesis. So when you, when that hypothesis is the only hypothesis that’s being funded and you’ve got all these researchers exploring that, um, it kind of keeps everybody’s eye off the ball of wait a minute. Might also be that nicotine is even more addictive in mentally ill people, right? It’s not right. So addiction and medication, they’re not the same, right? And so for years and years, people kept propagating the idea that smoking was an antidepressant, that it’s a cognitive enhancer. And if you look in psychiatric journals and the 19 eighties, the 1990’s, the 2000’s, anytime you find a paper that looks at smoking and tobacco use and mental illness and schizophrenia and depression, it’s always about tobacco being a medicine.

(34:14) Phil Lofton:

So one of the ways, I don’t want to jump too far ahead, but one of the ways that addiction psychiatry cuts through and gets the medical profession back on course is by proposing those alternate hypotheses. And saying maybe nicotine is causing another mental illness or is, is being, is, is creating a worsening effect of the mental illness. Maybe opioids aren’t this compassionate treatment for pain. And maybe you’re not a bad doctor for not wanting to give opioids to someone that is suffering. Maybe there’s another way, maybe you are avoiding giving them a mental illness by, you know, not giving them opioids.

(34:56) Andy Chambers:

Correct.

(34:57) Phil Lofton:

That’s really interesting.

(34:59) Andy Chambers:

That’s exactly right. And here’s the, here’s the link that’s really crucial in the conversation. Um, so part of where this alternative view, this not, you know, this kind of addiction view, that’s not addiction psychiatry, that’s not self medication or pseudo addiction, is that the idea that if you have a mental illness, then any addictive drug, just because you have the mental illness, any addictive drug is more addictive for that person. Right? And we already knew this was kinda true, I mean this is what the epidemiology says, the epidemiology is very clear on that, because think about this right now in the general population, only about 15 percent of us smoke. Yeah. Only 15 percent of adult smoke right now. But 50 percent of all cigarettes are smoked by someone with one some kind of psychiatric illness.

(36:02) Phil Lofton:

Wow.

(36:02) Andy Chambers:

Right? The rates of addiction to nicotine are much higher in people with mental illness.

(36:08) Phil Lofton:

Wow.

(36:09) Andy Chambers:

So let’s switch to another addictive drug. Different – totally different profile of intoxication. Let’s talk. Let’s go to alcohol. Yeah, we’re totally different from nicotine. Same thing, same thing, same thing. Let’s go to opiates. Yeah, totally different profile from nicotine, alcohol, same thing. There is a connection between mental illness and drug addiction. Right? So what we did the research in my lab and other labs in the early two thousands. So I started working on this in my medical school career and later on. Okay. If this is true, let’s do an experiment and we can’t do this with people because it’s not ethical, right? Because it has to be an experiment where you take a healthy animal, healthy subject and a mentally ill subject.

(37:03) Phil Lofton:

Yeah.

(37:04) Andy Chambers:

And it’s very simple. You just ask, okay. If you expose both subjects to the same amount of, of an addictive drug, yeah. Which one is more likely to get addicted, addicted, and which one is going to have a worst case of it, even though you’re exposing both subjects to the same amount of drug. So we started doing this research with animal models of mental illness and Lo and behold, the mental illness accelerates – biologically accelerates – the disease process of addiction. And it has nothing to do with the psychoactive properties of the drug.

(37:40) Phil Lofton:

Wow.

(37:40) Andy Chambers:

Right. So mental illness accelerates addiction and then addiction. When you start having it, it causes even worse. Mental illness. So there’s no room. You don’t need to talk about self medication in any of this conversation. Right? You don’t need the theory. It’s a, it’s a totally unnecessary hypothesis.

(38:14) Andy Chambers:

So, it’s not that you have to have a mental illness to get addicted. It’s not, you know. I need to point that out. Like because I’m not claiming that only people with psychiatric illness have addiction. I’m not saying that, I’m just saying that if you have the mental illness, your odds of getting addicted if you get exposed, is like two to six to eight times greater, like huge amplification. And we see that in the epidemiology. Right? And so you can begin to understand why is, you know, you can understand why this is on a biological level, not, not only, not only can you show it in animals that replicates the human, what we see in the human people and humans in the epidemiology, the American people, what you see on a big scale, and you can replicate the effect and individual animals, but the animals also give you the opportunity to get inside the brain to see how the diseases are more or less synergistically interacting.

(39:17) Andy Chambers:

Yeah. Right. And then that gives you a window into the disease of addiction itself, right? Because, you know, in any disease we study, we want to know what are the risk factors and when you understand a risk factor, you begin to understand part of the pathophysiology of it.

(39:33) Phil Lofton:

Yeah, yeah, absolutely.

(39:35) Andy Chambers:

Yeah. So, so when you kind of get to that link, that mental illness just, rather indiscriminately, accelerates addiction and it’s not drug specific. Yeah. Then you see this linkage between an addiction and mental illness and you’re like, oh my goodness, you have to treat both aggressively simultaneously in the same coherent treatment plan. Right.

(40:08) Phil Lofton:

So I think that goes to a pretty obvious place. You’ve got some good theories about what that looks like, that sort of intersectional care. Right? And it’s called the two by four model.

(40:21) Andy Chambers:

That’s right.

(40:22) Phil Lofton:

So tell me about the two by four model.

(40:23) Andy Chambers:

Okay. Well the two by four model takes that, that neuroscience, that basic neuroscience from the rats takes it from the epidemiology and says, you know, if these diseases are that tightly connected, we should have a network of clinics throughout Indiana, throughout the country that are capable of treating both conditions in an integrated way in one clinic by one treatment team. There should not be a segregation of mental health care from addiction care. Unfortunately, that’s what we got right now. But there’s no reason we can’t move to this integration within behavioral health where patients with basically any major addiction in any major mental illness can get, can walk into a building and get all that treated in whatever combination that got it without going somewhere else, without needing to do that. And if you do that, the care is going to be better and have more effective, better outcomes.

(41:25) Andy Chambers:

So to do that, you have to have some things. One of elements is the professionals on the team actually need to know how to do both. So you need psychiatrists that are trained in addictionology, those, that’s addiction psychiatry, those are addiction psychiatrists. When you have those individuals, they can train the nurses and the therapist to be cross proficient to treat mental illness and addiction. So really the addiction psychiatry group is fairly important. Keystone to this. But you know, you want all the professionals on the team in this kind of clinic to be comfortable and competent and in fact expert at both mental illness and addiction. So you have this professional group. It’s a team. What happens is any combination, the patient presents with PTSD and nicotine addiction, alcohol, bipolar disorder, Nicotine, OCD, schizoaffective disorder, any of these combinations, they come in the door and that same team can do it all.

(42:36) Andy Chambers:

So what does that team need? They need four components as to why we call it the two by four Model. Two on one dimension, meaning take care of both mental illness and addiction. Four, on the horizontal dimension is there are for treatment components. The clinic has got to have to to do this kind of care. First of all, they need the right diagnostic tools, which means that the diagnosticians, the addiction psychiatrist, the other team members, when they do assessments, they need to pay attention to the full spectrum of mental illness and addiction. You know, they can’t say, well, this is a bipolar treatment clinic, so I’m not going to even pay attention to your drinking. Yeah, or they can’t say I’m here to treat your opiate addiction, but anything, any other addiction you got or any other mental health, that’s not my job, so I’m not paying attention to that, that, that’s over in this clinic. We reject that, right?

(43:38) Phil Lofton:

Yeah.

(43:39) Andy Chambers:

So a full comprehensive workup and then, um, diagnostic outcome measures, right? So constant urine drug screening, constant prescription drug monitoring with INSPECT or whatever the system is

(43:55) Phil Lofton:

just for our listeners that aren’t in the profession, what is INSPECT?

(43:58) Andy Chambers:

INSPECT is a way for us to monitor the way patients are being prescribed controlled substances over time actually. Um, and you know, other other outcome measures, you know, they’re rating scales you may use periodically, but you know, really repeated exams, you know, it’s not that you initiate treatment, you never reexamine the patient. I mean, in a way, I’m just describing the way the rest of medicine works. So when I’m kind of saying is can we, can we actually have behavioral health operate in the house of medicine with the kind of same standards because it is a, these are medical issues of the brain.

(44:35) Phil Lofton:

You know, what a revolutionary idea.

(44:37) Andy Chambers:

And so, so then there’s, that’s the diagnostic. The next dimension that, you know, one of the four key domains of components is psychotherapies. You have to have an array of psychotherapies that are evidenced based for treating mental illness and drug addiction groups and individual therapies and different subtypes. So that’s the way you individualize the care you can. Some patients are going to have individual psychotherapy, some are going to have groups, some are going to have both, some are going to have neither it individualized to the patient. It’s not about, you know, a system that only gives one treatment to everybody, one size fits all because that doesn’t happen anywhere else in medicine. Why should that be the standard in paper health? Right. So, right, okay. The third, third component is medications.

(45:33) Andy Chambers:

You have to have medications that are evidence space are FDA approved for the entire spectrum of addiction and mental illness. Why should you have a clinic that only provide w w rather when you have a clinic that only provides one medication for one illness? Then that’s kind of this factory rubber stamping, not individualizing care, inflexible can’t really treat most people

(46:04) Phil Lofton:

And it Kinda is the model that got us into this situation, right? It’s like pain clinics that operated as pill mills?

(46:11) Andy Chambers:

In part, right? Just throw opiates at everybody walks in the door. So you kinda need a medications that treat the full spectrum of mental illness and the full spectrum of addiction. That’s, that sounds revolutionary, but why should it be? Because if you go to a primary care doc, it’s not like they’re going to just prescribe everybody the same antibiotic no matter what you come in with, right?

(46:39) Andy Chambers:

Right. At primary care docs know how to prescribe all kinds of stuff and know how to do all kinds of diagnostic. So in a way I’m describing a integration of behavioral health that is broadly capable of treating all these problems under one roof by one team. So the final piece, this fourth component of the two by four model is the docs, and the team members, the addiction psychiatrist and the other, you know, nursing therapists need to be able to communicate to people on the outside of the clinic to be proactive in protecting the treatment of their patients. They have to be communicated, they have to be talking to the criminal justice system, they have to be talking to other doctors, they have to be active in communicating to recruit the right support for the treatment mission that’s happening within the clinic. And this is really important because the war on drugs and the criminalization of mental illness and addiction is not a treatment approach.

(47:46) Andy Chambers:

It’s an anti treatment. The iatrogenic epidemic is the inappropriate prescribing controlled substances. So we have to be proactive to stop outside doctors from relapsing our patients. We have to be proactive in communicating with insurance companies to try to get them to support what we’re doing instead of blocking it. Right? So now imagine what’s happening in the two by four model on the two dimension, two by four, all mental illness, all addiction in whatever combination being treated by the same team who’s doing the diagnostic tests. Providing a psychotherapy is providing the medications and the outside communications and consultations all one team. So all that data is integrated. Yeah. And the patient, the team takes full responsibility for the patient. There is no other, you know, in, in a fragmented system, a patient comes in and has mental illness. Well, if there’s an addiction in a fragmented system that only treats, for example, schizophrenia will, if the patient’s using cocaine, marijuana, well we don’t treat that, you know, we only treat schizophrenia. So if they’re not doing well, that’s not really on us. So we’re just keep treating the schizophrenia regardless of the outcome. Right?

(49:08) Phil Lofton:

Yeah.

(49:08) Andy Chambers:

We just kind of add more meds for schizophrenia. It’s kind of what we do. That’s the lever we press. If the patient doesn’t do well, because their addiction, well, you know, that’s not on us. We are building is about treating schizophrenia. You see what I’m saying? But wait a minute, but they’re using marijuana and cocaine which worsen schizophrenia, you know, or, or let’s go to the addiction side. Right? So, you know, a patient who is really having a hard time with addiction, um, they’re, they’re having trouble with compliance, they’re acting strange at times. Well, you know, that patient, I don’t know what’s going on with them. They just don’t want it. They don’t want to participate in care. Yeah. You see what I mean?

(49:50) Andy Chambers:

Because, when really what’s going on is there’s a mental illness that’s part of the picture that, that treatment system is ignoring. And so they don’t take responsibility for that part. They kind of blame the patient and they themselves never have to get better. They don’t have to take responsibility. So the patients aren’t being taken care of. No one with these patients is stepping up saying this is our job to take care of this person and to, you know, do our best to keep them well holistically, to tell the criminal justice system, hey, we got this person in our care. You don’t need to punish them. We got this.

(50:32) Phil Lofton:

Yeah.

(50:33) Andy Chambers:

Or to, you know, call up the hospital, look, we’re, you know, we’re taking care of this mental illness. We’re taking care of this addiction. So pleased when they come to the ER, do not prescribed that hydrocodone and they show up.

(50:45) Andy Chambers:

Right. But see what I mean? So imagine if you had clinics like this in a region statewide, nationally. It would be-

(50:57 ) Phil Lofton:

It’s pretty revolutionary.

(50:58) Andy Chambers:

Hopefully.

(50:59) Phil Lofton:

Yeah. Wow. Wow.

(51:02) Andy Chambers:

So the two by four model concept, it’s been around. Integrated dual diagnosis care is the, is the term and there’s evidence for it, but it never got adopted. Just never adopted. Evidence doesn’t translate well on behavioral health. Just doesn’t, I mean, you know, lottery. Okay. The silo between science and clinical care. Yeah, it’s there in behavioral health, lots of evidence for all kinds of things that never ended up being done clinically. So there’s a whole other set of problems with that. But you know, again, lack of funding, lack of insurance coverage, lack of, you know, emphasis on behavioral health as a core part of primary, primary preventative medicine as well, which is what it is. So all these things. But I think the other, the other thing that wasn’t quite in place was this biological link now, right? We really have a better handle on knowing that mental illness and different addictions are connected in the brain so it doesn’t make sense to provide care that split out.

(52:23) Phil Lofton:

Yeah. So the, I usually ask this question towards the end of the interview and it’s super obvious with yours, the usual question is, well, what comes next and addiction in addiction, psychiatry, and it seems like the obvious answer at the end of this interview is we need to invest more funding in two by four type model clinics. We need to change the way that we compensate so that those sorts of clinics can be incentivized so that they can receive the proper, uh, you know, compensation to operate because it is, it is specialized. It is unique because it’s specialized and unique, it’s powerful and it can get good outcomes. Okay. What else?

(53:05) Andy Chambers:

Well, and along along with those things, because in a way you kind of mentioned, you know, the insurance reimbursement for this kind of care needs to be stepped up and bear barriers that would prevent the proper reimbursement for the care removed, I think. I think, you know, trained workforce. So in behavioral health we have to really look bringing more people in psychiatry into addiction, psychiatry, getting more people in psychiatry and understand that it’s really hard to treat the spectrum of illnesses that you’re interested in without being open to treating the addiction side of it as well. Yeah. So, you know, and that people need to be trained in that. This is not something that, um, it, it really is a skill. It really requires formal residency and fellowship training and it requires certification, you know, so that people know who’s been properly trained.

(54:02) Andy Chambers:

And so I think building up the workforce, building up the infrastructure and making sure insurance coverage happens for this care. Now, a lot of people are gonna say, well that is huge amount of money. You’re talking about huge investment and what I can say that as, are you kidding me? Our healthcare system spends double any other country in the world and we’re getting worse outcomes. And what, what’s the real root of that? You know, to what extent is that related to our opioid epidemic? You know what, to what extent is all this? Addiction isn’t the number one cause of premature illness and death. Yeah. Right. And we’re doing very little for that and yet the expenses of treating the medical consequences of all this addiction and mental illness that we’re not treating is, is vast and it’s unsustainable. Think about like the part of our state budgets, right?

(54:58) Andy Chambers:

That go to building prisons and delivering medical care for the consequences of untreated addiction. We’re, it’s eating up our state budget. So what, what are, what are state governments doing? They’re basically putting education on the backs of, of citizens. So it’s affecting all of us, you know, our, our, our ability to, to go to college to go to professional school. It’s more on the backs of individual families because the government can’t afford to help. Help us out with that education. Right? Because our governments are spending incredible, vast sums of dollars on prisons and runaway healthcare costs for not treating addiction.

(55:41) Phil Lofton:

Right. Fascinating. Wow. There is so much down back in that conversation. The way that we split medical care that belongs together, the way that we’ve approached and discussed addiction. I could go on, but one thing jumps out to me right now is the way that we track patients’ information across health systems. There are serious blind spots in the way we record patient data that we need to address. Join us next time when we talk with some of the leaders in medical informatics and data science about how we can change the way we use patient data to make a dent in the opioid crisis. We’ll see you then on The Problem. Music this episode was from Everlone. Our theme and additional musical cues in this episode, were written and performed as always by Susanna Washington and the Scaredy Cats. The Problem is produced at studio 132 IN the Regenstrief institute in Indianapolis, Indiana, where we connect and innovate to provide better care and better health. Learn more about our work and how you can get involved at regenstrief.org And see bonus content from this episode, including sources, pictures and more at regenstrief.org/theproblem.

Bonus Content

Andy discusses addiction psychiatry with IU Health: https://iuhealth.org/news-hub/dr-chambers-discusses-mental-illness-addiction

A presentation from the 3rd Annual Prescription Drug Abuse Symposium Targeting Strategies to Curb the Epidemic in Indiana Indianapolis, December 19, 2012: https://www.in.gov/attorneygeneral/files/BreakoutChambers.pdf